This review was originally published by Engelsberg Ideas in April 2024.

In December 1958 an All-African People’s Conference was held in Accra, capital of the newly independent Ghana. It brought together delegates from 28 African countries, many of them still European colonies. Their purpose, according to Ghanaian prime minister Kwame Nkrumah, was ‘planning for a final assault upon Imperialism and Colonialism’, so that African peoples could be free and united in the ‘economic and social reconstruction’ of their continent. Above the entrance of the community centre where the conference took place, there was a mural which seemed to echo Nkrumah’s sentiment. Painted by the artist Kofi Antubam, it showed four standing figures along with the slogan: ‘It is good we live together as friends and one people.’

The building was a legacy of Ghana’s own recent colonial history. During the 1940s the UK government’s Colonial Development and Welfare fund had decided to build a number of community centres in what was then the Gold Coast. Most of the funding would come from British businesses active in the region, and the spaces would provide a setting for recreation, education and local administration. The Accra Community Centre, neatly arranged around two rectangular courtyards with colonnaded walkways, was designed by the British Modernist architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry. Antubam’s mural calling for amity reads somewhat differently if we consider the circumstances in which it was commissioned. The United Africa Company, the main sponsor of the project, was trying to repair its public relations after its own headquarters had been torched in a protest against price fixing.

The Accra Community Centre is emblematic of the ambiguous role played by Modernist architecture in the immediate post-colonial era. Like so many ideas embraced by the elites of newly independent states, Modernism was a western, largely European doctrine, repurposed as a means of asserting freedom from European rule. ‘Tropical Modernism’, a compelling exhibition at London’s V&A, tries to document this paradoxical moment in architectural history, through an abundance of photographs, drawings, letters, models and other artefacts.

Drew and Fry are the exhibition’s main protagonists, an energetic pair of architects who struggled to implement their vision in Britain but had more success in warmer climes. In addition to the community centre in Accra, they designed numerous buildings in West Africa, most of them educational institutions in Ghana and Nigeria. In the course of this ‘African experiment’, as Architectural Review dubbed it in 1953, they developed a distinctive brand of Modernism, of which the best example is probably Ibadan University in Nigeria. It consisted of horizontal, geometric volumes, often raised on stilts, with piers running rhythmically along their facades and, most characteristically, perforated screens to guard against the sun while allowing for ventilation.

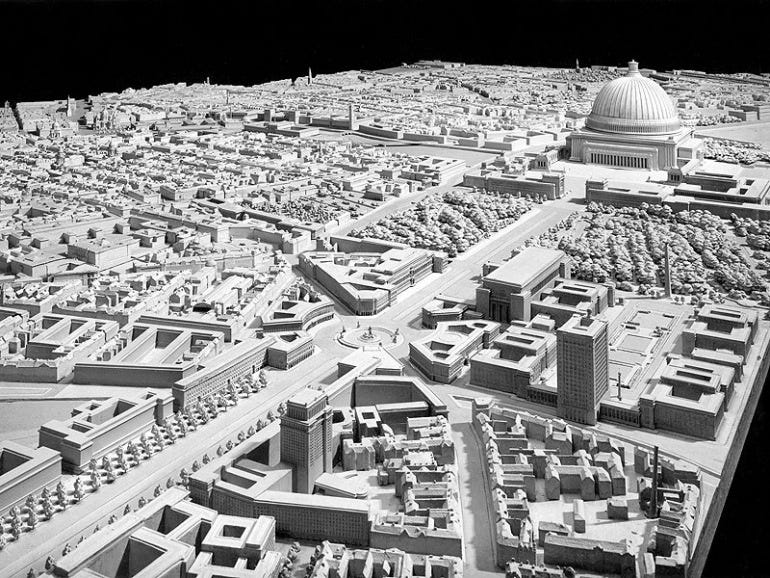

On the basis of this work, Drew and Fry were invited to work on the planning of Chandigarh, the new capital of the state of Punjab in India, which had just secured its own independence from Britain. Here they worked alongside Le Corbusier, the leading Modernist architect, on what was undoubtedly one of the most influential urban projects of the 20th century. Drew and Fry also helped to establish Tropical Architecture courses at London’s Architectural Association and MIT in Massachusetts, where many architects from post-colonial nations would receive training.

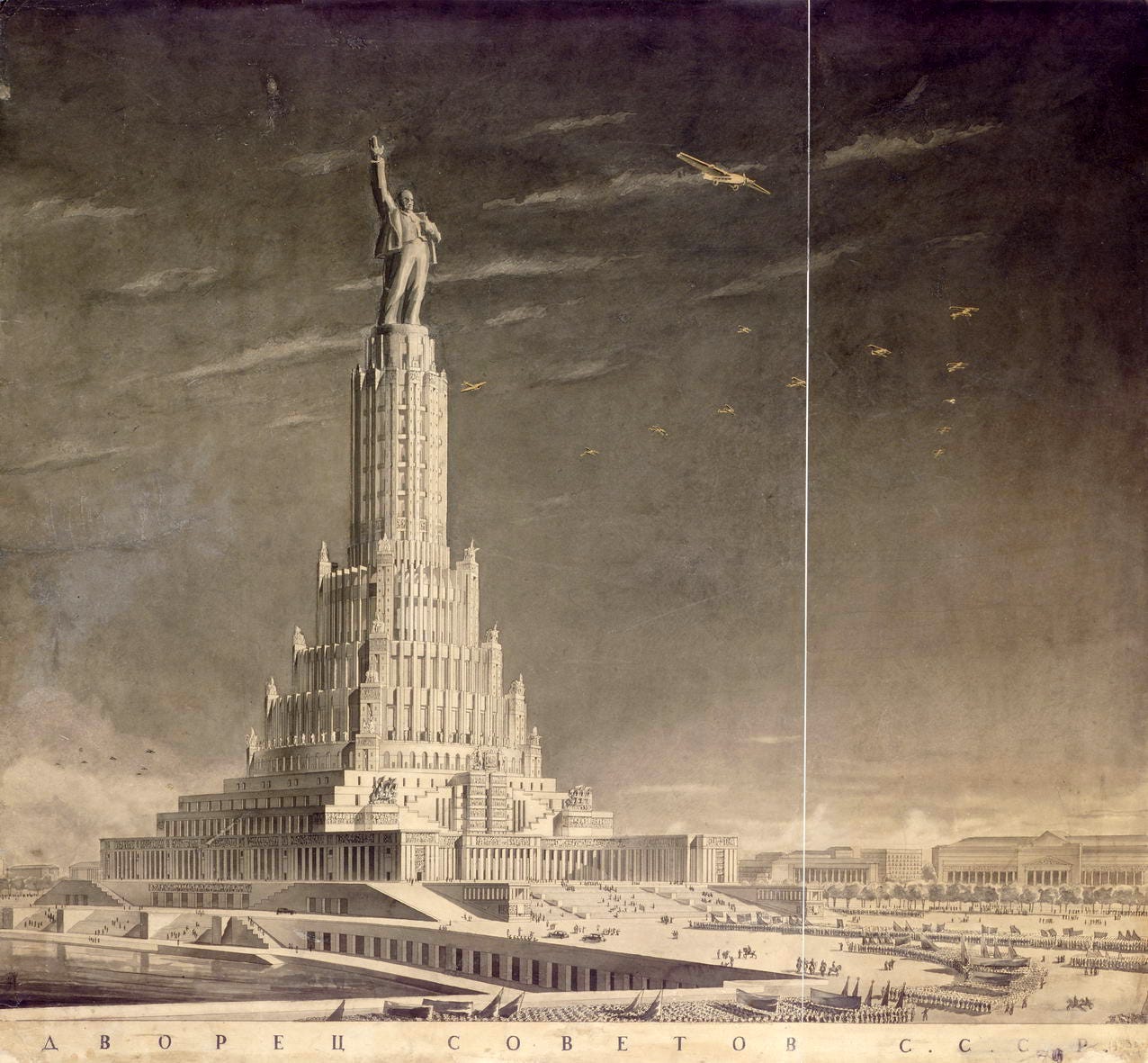

Not that those students passively accepted what they were taught. The other major theme of the exhibition concerns the ways that Indian and Ghanaian designers adopted, adapted and challenged the Modernist paradigm, and the complex political atmosphere surrounding these responses. Both Nkrumah and Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, preferred bold and bombastic forms of architecture to announce their regimes’ modernising aspirations. This Le Corbusier duly provided, with his monumental capitol buildings at Chandigarh, while Nkrumah summoned Victor Adegbite back from Harvard to design Accra’s Black Star Square. In India, however, figures such as Achyut Kavinde and Raj Rewal would in the coming decades forge their own modern styles, borrowing skilfully from that country’s diverse architectural traditions. At Ghana’s own design school, KNUST, it was the African American architect J Max Bond who encouraged a similar approach to national heritage, telling students to ‘assume a broader place in society, as consolidators, innovators, propagandists, activists, as well as designers’.

As is often the case, the most interesting critique came not from an architect, but an eccentric. In Chandigarh, the highway inspector Nek Chand spent years gathering scraps of industrial and construction material, which he secretly recycled into a vast sculpture garden in the woods. His playful figures of ordinary people and animals stand as a kind of riposte to the city’s inhuman scale.

One question raised by all of this, implicitly but persistently, is how we should view the notion of Modernism as a so-called International Style. In the work of Drew, Fry and Le Corbusier it lived up to that label, though not necessarily in a good way. Certainly, these designers tried diligently to adapt their buildings to new climatic conditions and to incorporate visual motifs from local cultures. In light of these efforts, it is all the more striking that the results still resemble placeless technocratic gestures, albeit sometimes rather beautiful and ingenious ones. We could also speak of an International Style with respect to the ways that these ideas and methods spread: through evangelism, émigrés and centres of education. It’s important to emphasise, which the V&A show doesn’t, that these forms of transmission were typical of Modernism everywhere.

By the 1930s, Le Corbusier was corresponding or collaborating with architects as far afield as South Africa and Brazil (and the latter was surely the original Tropical Modernism). Likewise, a handful of European exiles, often serving as professors, played a wildly disproportionate role in taking the International Style everywhere from Britain and the US to Kenya and Israel.

If Modernism was international, its Tropical phase shows that it was not, as many of its adherents believed, a universal approach to architecture, rooted in scientific rationality. Watching footage at the exhibition of Indian women transporting wet concrete on their heads for Chandigarh’s vast pyramids of progress, one is evidently seeing ideas whose visionary appeal has far outstripped the actual conditions in the places where they were applied. As such, Modernism was at least a fitting expression of the ill-judged policies of rapid, state-led economic development that were applied across much of the post-colonial world. Their results differed, but Ghana’s fate was especially tragic. A system where three quarters of wage earners worked for the state was painfully vulnerable to a collapse in the price of its main export, cocoa, which duly came in the 1960s. Nkrumah’s regime fell to a coup in 1967, along with his ambitions of pan-African leadership and the country’s Modernist experiment. Those buildings had signified ambition and idealism, but also hubris.